How to deliver data quickly

One of the most effective ways to increase the speed of data delivery is to reduce the amount of data being transferred. Of course, we should always start by reviewing the API endpoint model - is there anything we can omit, or are some fields not being used, etc.? But once that stage is over, the next thing we can do is batching and compression.

Batching

The idea of batching is very simple: instead of sending each request or message separately we can group them together into a single request. How does this help?

There are many benefits:

- Batching increases throughput - we know that every request consumes resources. Usually it is better to make fewer requests with more data as opposed to make more requests with fewer data:

- No need to pass HTTP headers with each request

- No need to establish multiple connections and allocate resources for each of them

- No need to create multiple threads to process request with assumption that server is using thread-per-request model

- Fewer requests also mean fewer dollar cost - this is particularly true for public cloud services with pay per-request pricing model - the fewer request we make, the less money we pay for services.

- Fewer chances of being throttled - services often protect themselves from being abused by clients that send too many requests in a short period of time.

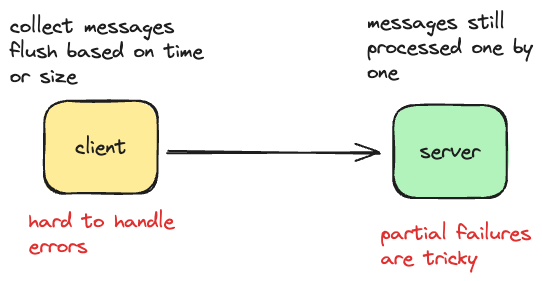

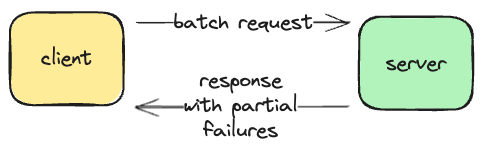

However, batching introduces complexity on both the client and server side.

- On the client side we need to accumulate messages in a buffer before sending out and flush the buffer based on time or size (which one comes first) - all this make the client harder to implement and configure;

- On the server side, messages in the request are processed one by one and partial failures are possible: first four messages were processed successfully, but on fifth - message handler failed. What should we do? Continue processing? Report failure? Should we rollback already processed messages?

That’s why it’s so much easier with a single message per request: request was sent and in the case of failure we definitely know which message was failed and can easily retry an entire request.

Looks like we have two options of handling batch request on server:

- Treat the entire request as a single atomic unit - request succeeds only when all nested operations complete successfully;

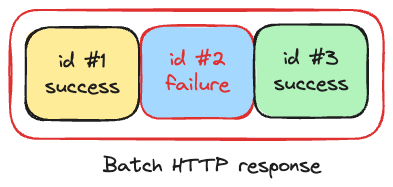

- Treat each nested operation independently and report back failures for each individual operation - service processing the request tries to make as much progress as possible. This approach is more common in practice.

What format should we use for batch request?

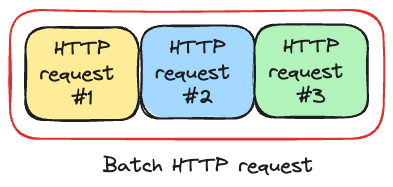

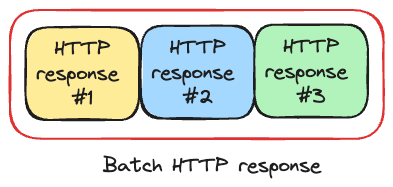

Batch multiple requests into a single call - combine multiple HTTP requests into one standard HTTP request. Think of it like a concatenation of individual requests. We take multiple HTTP requests with headers & bodies and then concatenate them using separator. The server process each HTTP request and returns single standard HTTP response which contains status codes for each individual request. Many Google APIs support batching, and they use this format, for example Google Drive batch API: https://developers.google.com/drive/api/guides/performance#batch-requests

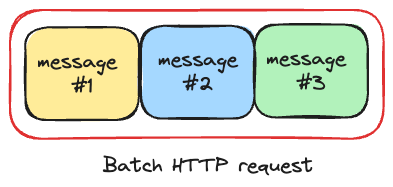

Batch multiple resources into a single call - A good example of this approach is AWS SQS batch API which submits multiple messages to specified queue: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AWSSimpleQueueService/latest/APIReference/API_SendMessageBatch.html. In this approach instead of concatenating HTTP requests, we combine multiple messages. A server returns back a standard HTTP response that contains a list of results for each individual message. Each result in the list contains identificator of message and status - whether message was successfully queued or not.

Batch request result in combination of successful and unsuccessful operations. Now let’s get back to client and take a look at how we can handle partial success results:

Retry the entire batch request - perfectly valid option if each individual message is idempotent. The server will replay all operations one more time and this will not have an effect on previously succeeded operations but failed operations will get a chance to succeed. The big advantage of this option is that it is pretty easy to implement it on client side.

Retry each failed operation individually

Create another batch request containing only failed individual operations

The last two options require a bigger effort on the part of the client. The client has to check each individual operation failures and create one or more new requests. However, these two options don’t require server to be idempotent.

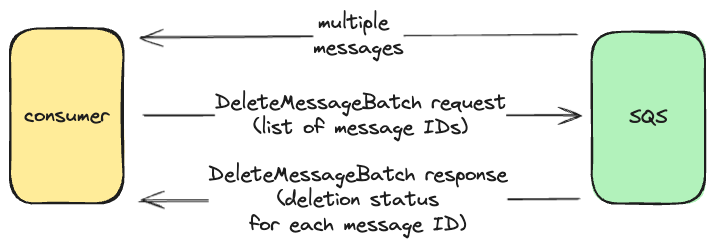

Let’s take a look on SQS batch API when retrieving messages from SQS we can configure a pull request to return multiple messages up to 10.

Consumer is responsible for deleting processed messages and SQS provides a batch API to do this: delete messages batch API, where a list of message identifiers is specified in a batch request. The response of delete messages batch API contains status of deleting operation for every message. As you know already, fail to delete message will not be removed from the queue and will be retrieved by this or other consumers later when visibility timeout will be expired on such messages. So the consumer has to scan through delete messages batch response and check for individual message deletion failures. If at least one failure is identified, the consumer can use any of these three options mentioned above.

It’s worth mentioning that Kafka heavily relies on batching on both sides: when producer is sending messages to a broker and consumer when retrieving messages. Batching is one of the secrets that makes Kafka very high-throughput.

Compression

Data compression is the process of reducing the size of data. Information is encoded using fewer bits than the original representation.

Compression has many benefits:

- we have fewer data to transfer that means lower latency and higher throughput while transmitting messages over the network since we have less data to transfer

- we have fewer data to store, which means more messages can be stored on disk and both reading from disk and writing to disk becomes faster

- reduce dollar costs when we use public cloud services, since the cost of data transfer for many cloud services is based on the total amount of data served: serving compressed files is less expensive than uncompressed files.

We can find compression everywhere:

- web-server compress HTTP data for faster transfer over the network and browsers then download compressed data and decompress it

- databases compress data, so it takes less disk space to store

- LSM-tree based databases (RocksDB, Apache Cassandra etc.) can be configured to compress SS-Tables: on reads database locates compressed chunk on disk and then decompresses it.

- messaging systems heavily use compression as well: producers compress messages, send them to the broker, which then transfers compressed data to consumers. Consumers know the compression format and decompress messages.

Here are some more facts about compression:

- Compression becomes generally more effective as the data size increases. Compression loves batching: rather than compressing individual message or request, it’s more efficient to batch them together and then compress.

- Compression and decompression processes consumes computational resources (CPU), but CPU is one of the easiest resources to scale rather than network or disk IO, many distributed systems prefer to pay this price.

There are two types of compression:

- lossy - loose data by permanently eliminates bits of data that are redundant or unimportant. Most commonly used to compress audio, images, video and especially in video streaming where data size and result data transfer latency can be more important than quality.

- lossless - no information is lost. File is restored to its original state without loosing any bits of data: HTTP request/response compression, compression used by databases and messaging systems. Obviously we can’t afford to loose data in these scenarios.

There are many compression algorithms often makes trades-off in these areas:

- compression speed - how fast the compression algorithm compresses data. This characteristic is important for write-heavy applications.

- decompression speed - how fast the compression algorithm decompresses data and this is important for read-heavy applications.

- compression ratio - ratio the uncompressed data is reduced by. This is important for applications that store a lot of data on disk.

For example:

- Gzip is popular for HTTP compression and is known for large compression ratio, but compression and decompression performance is not great.

- Snappy, created by Google and used in BigTable and MapReduce, is fast for both compression and decompression, but compression ratio is lower than Gzip.

- Zstandard, created by Facebook, provides high compression ratio together with high compression and decompression speed. This algorithm is widely adopted by the industry.